Shaping the Future of Healthcare in Kenya

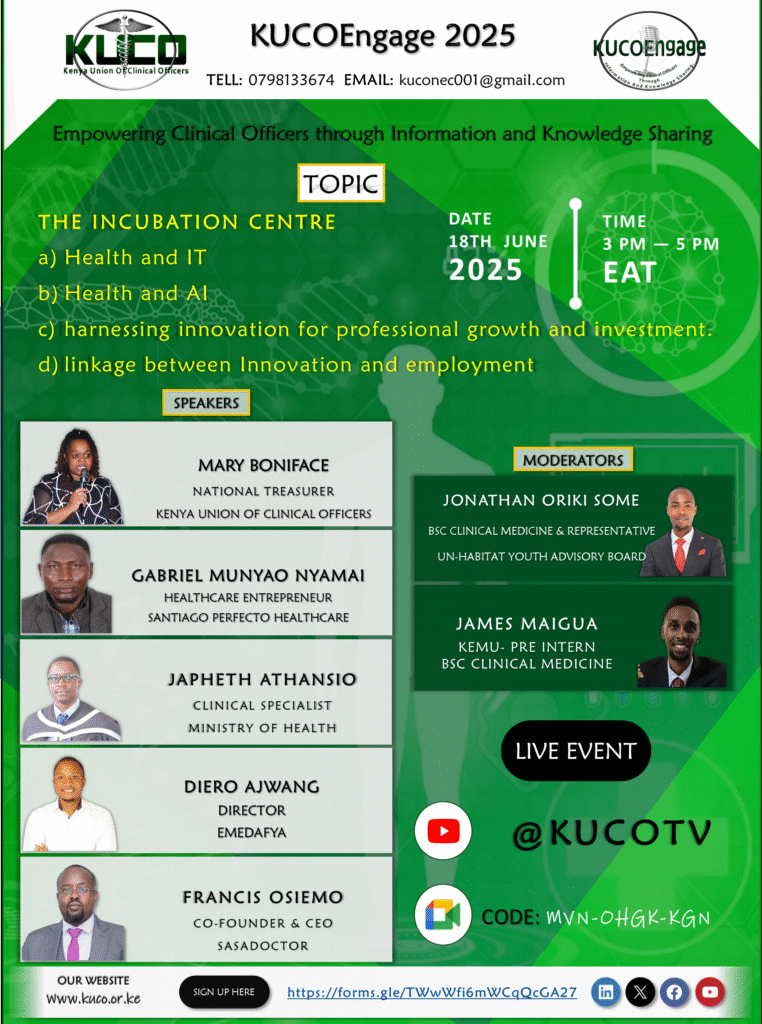

The intersection of health, technology, innovation, and professional growth is rapidly redefining healthcare delivery. In a recent KUCOEngage session, a panel of trailblazing professionals and healthcare entrepreneurs explored key trends and challenges, offering profound insights into the evolving landscape of medical practice, particularly for Clinical Officers in Kenya. This article highlights discussions on health and IT, artificial intelligence, and harnessing innovation for professional growth and employment within healthcare innovation in Kenya.

The Digital Transformation of Healthcare: Health Information Technology (HIT)

The conversation began with a deep dive into Health Information Technology (HIT) and its impact on service delivery. Ms. Mary Boniface, KUCO National Treasurer and a Clinical Officer specialized in Medical Diagnostics and Sonography, highlighted the monumental shift from paper-based records to Electronic Health Records (EHRs). She reminisced about the challenges of misplaced records and inefficient processes in the early 2010s, contrasting them with the current benefits of digitization. EHRs have been a “game changer,” particularly in sonography, enhancing diagnostic accuracy and enabling seamless peer-to-peer consultations through digital systems. This has significantly reduced patient waiting times and improved clinical decision-making, a crucial aspect of healthcare innovation in Kenya.

Telemedicine and telehealth emerged as another crucial aspect of HIT. Mr. Harun Dierro, Director of EMEDAFYA, explained how their app and website facilitate healthcare access by connecting patients with providers regardless of geographical distance. This addresses the challenges of distance and offers convenience, even for emergency care. He emphasized that telemedicine is “the way to go” and a “big game changer,” despite the persistent challenge of internet infrastructure in certain parts of Kenya.

However, the journey to technological integration in healthcare is not without its hurdles. Mr. Francis Osiemo, Co-founder and Executive Director of SASAdoctor, elucidated the significant challenges faced by digital health enterprises. The cost of developing and hosting robust applications, coupled with navigating multiple regulatory bodies (Ministry of ICT, Ministry of Health, and the Digital Health Act), presents substantial financial and logistical burdens. Furthermore, patient adoption remains a key challenge, as Kenyans exhibit unique consumption habits for healthcare services. Interestingly, SASAdoctor has observed higher adoption rates among elderly patients, who actively seek healthcare solutions, compared to younger demographics. Mr. Osiemo stressed the importance of understanding the local market to ensure successful implementation of healthcare innovation in Kenya.

Data security and privacy are paramount in the digital health era. Mr. Gabriel Nyamai of Santiago Perfecto Healthcare underlined the legal implications of mishandling patient data, emphasizing the need for computerized systems where access is strictly authorized. Mr. Francis Osiemo further elaborated on the regulatory landscape, citing the Digital Health Act and the Office of the Data Protection Commissioner as crucial frameworks for compliance. He also mentioned ISO standards and the need for a unified approach to licensing for virtual care.

Artificial Intelligence: A Tool for Empowerment, Not Replacement in Kenyan Healthcare

The discussion then shifted to Artificial Intelligence (AI) and its role in healthcare. A common concern among professionals is whether AI will “deskill” or “endanger” their work. Mr. Harun Dierro, in a comprehensive presentation, firmly stated that AI is “a tool to support your work,” not a replacement. He illustrated AI’s transformative potential, from faster diagnoses and smarter treatments to better data utilization. He detailed various AI application parameters, including:

• Diagnostic AI

• Treatment Support AI

• Patient Follow-up AI

• Administrative AI

• AI-Assisted Surgeries and Procedures

• Preventive Health AI

Kenyan examples like MD Medicine, connecting patients to Clinical Officers, and SASAdoctor’s features (finding practitioners, scheduling, video calls, digital prescriptions) demonstrate local AI integration. The future, according to Mr. Dierro, involves widespread adoption of AI agents, which can automate tasks like prescription refills, lab result interpretation, and patient triaging, standardizing healthcare across different facilities. This directly contributes to healthcare innovation in Kenya.

However, challenges persist. Mr. Dierro highlighted the lack of AI expertise and infrastructure in Kenya, with only 50% readiness for AI adoption. The high cost of AI tools and the fact that tools developed in other regions may not be effective in Kenya due to unique co-existing conditions are significant barriers. Furthermore, there are training gaps, with many Clinical Officers unaware of AI tools and agents, and many who do know them, do not know how to use them effectively.

Despite these challenges, Mr. Dierro emphasized the ethical considerations: data privacy concerns, bias in AI tools (feeding garbage in, getting garbage out), and the crucial need for human oversight. He concluded by asserting that “AI will grow whether we like it or not,” and Clinical Officers, as the first point of contact, are “key personnel in integrating AI safely in Kenya.” The key is exploration, engagement in training, and testing small AI tools.

Ms. Mary Boniface reiterated that AI is not about replacement but “human – AI collaboration.” She stressed that training institutions must integrate AI coursework into core curricula. She also highlighted the critical need for local data sets to ensure AI models are relevant to African populations, and warned against “over-reliance” that could diminish the crucial aspects of the human touch – humanity, empathy, and compassion in medical practice – attributes that AI does not possess.

Harnessing Innovation for Professional Growth and Employment in Kenyan Healthcare

The final segment focused on harnessing innovation for professional growth and investment, and the linkage between innovation and employment. Mr. Francis Osiemo identified key trends in the investment landscape of telemedicine. He emphasized a shift towards “value-based care,” where solutions solve real problems and provide tangible value to users. The integration of AI and automation into daily practices is crucial for efficiency and cost-saving. He also stressed the importance of “interoperability and data integration” between systems to facilitate reporting and leverage existing applications, reducing development costs, thereby driving healthcare innovation in Kenya.

Mr. Osiemo observed a “hybrid care model” trend, where patients might start with physical consultations and then follow up virtually, gradually building trust in remote care. He encouraged working with insurance companies to boost investor confidence and exploring “business-to-business” and “business-to-government” partnerships for scalability. Furthermore, he advocated for Clinical Officers to become consultants in Digital Health Regulations, creating new income streams. The localization of AI solutions to cater to Kenya’s diverse linguistic and cultural landscape was also highlighted as a vital area for collaboration among Clinical Officers.

Mr. Japheth Athanasio, a Clinical Specialist at the Ministry of Health, offered a comprehensive framework for Clinical Officers venturing into entrepreneurship, emphasizing the importance of understanding the broader healthcare system’s building blocks. These include:

• Governance: Adhering to policies and legal frameworks.

• Healthcare Financing: Understanding costs, pricing, budgeting, and GDP to assess market demand for services.

• Workforce: Recognizing the need for multidisciplinary teams and specialized healthcare workers.

• Monitoring and Evaluation: Utilizing data to track outcomes, impacts, and processes for effectiveness and efficiency.

• Infrastructure: Ensuring appropriate requirements, governance, and legal frameworks are in place.

• Service Delivery: Identifying the specific area of healthcare (prevention, promotion, curative, diagnostics, rehabilitation, referral) to innovate within.

Mr. Athanasio particularly stressed the importance of uniform digitized data using common terminologies (Kenya Digital Health Dictionary, ICD-11) to enable seamless data exchange between different healthcare systems. He emphasized that AI relies on quality data, and inaccurate or scarce data will lead to unreliable solutions. He also raised concerns about data hosting, advocating for local servers within Kenya’s jurisdiction to ensure compliance with data protection laws, and advised aspiring entrepreneurs to institutionalize themselves with data hubs, understand regulatory institutions like the Digital Health Authority, and focus on delivering value to patients. Mr. Athanasio highlighted the “scarcity of knowledge” in health informatics and economics, encouraging Clinical Officers to pursue further education in these areas. While acknowledging the entrepreneurial opportunities, Mr. Athanasio cautioned against solely focusing on “making a killing” financially, as sustainability in healthcare is often challenging due to numerous regulatory complexities. He cited the 2023 census report, indicating only 31% of Kenyan facilities are ready for digitization, underscoring the challenges of data quality due to inadequate human resources for converting manual data.

Ms. Mary Boniface addressed the issue of “professional stagnation” among Clinical Officers, attributing it to challenges in career pathways, slow absorption into employment, uncompetitive rates in the public sector, and general perceptions of their professional scope. She sees innovation as a powerful solution, urging Clinical Officers to “shift their mindsets from employment is the only way out” and actively identify gaps in the system to create sustainable solutions. The biggest challenge, she noted, is moving from “ideation to commercialization” and making business ideas viable ventures. She called for workshops and collaborative efforts to empower clinicians in transforming their innovative ideas into successful businesses.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the KUCOEngage session served as a powerful reminder that the future of healthcare, particularly healthcare innovation in Kenya, is undeniably digital and AI-driven. While challenges related to cost, infrastructure, adoption, and data quality exist, the opportunities for innovation and professional growth are immense. For Clinical Officers, embracing AI is not a choice but a necessity for relevance. The key lies in understanding the technology, collaborating with stakeholders, localizing solutions, and adhering to set regulatory frameworks and standards.

https://shorturl.fm/AvRL8

https://shorturl.fm/Vv0SL

https://shorturl.fm/Vv0SL

https://shorturl.fm/HhLL1

https://shorturl.fm/0B3sQ

https://shorturl.fm/fO5OJ

https://shorturl.fm/VVzWa

https://shorturl.fm/6IKQH

https://shorturl.fm/nw1kY

https://shorturl.fm/o7ap2

https://shorturl.fm/LOkgE

https://shorturl.fm/IegeZ

https://shorturl.fm/ZKpzL

https://shorturl.fm/P2puG

https://shorturl.fm/oMmoe

https://shorturl.fm/rQP5v

https://shorturl.fm/9IyV6

https://shorturl.fm/nBQz5

https://shorturl.fm/dS4lr

https://shorturl.fm/X7oOJ

https://shorturl.fm/RIxuT

https://shorturl.fm/2NLKV

https://shorturl.fm/Rz9mr

https://shorturl.fm/waNb8

https://shorturl.fm/pUB8T

https://shorturl.fm/cDBZ3

https://shorturl.fm/tacqK

https://shorturl.fm/DRUl1

https://shorturl.fm/qfve2

https://shorturl.fm/aoBOa

https://shorturl.fm/jGvGT

https://shorturl.fm/eY52G

https://shorturl.fm/GHmni

https://shorturl.fm/S8faj

https://shorturl.fm/J3lIB

https://shorturl.fm/LCjxE

https://shorturl.fm/BxfnX

https://shorturl.fm/K2DI4

https://shorturl.fm/Tp7sh

https://shorturl.fm/xmly6

https://shorturl.fm/Obu3V

https://shorturl.fm/CvVoj

https://shorturl.fm/sE2wj

https://shorturl.fm/3uvLP

https://shorturl.fm/8bBSI

https://shorturl.fm/z9qZ4

https://shorturl.fm/yPY1Q